(Any unauthorised quotations, copying, or use of the following is strictly prohibited)

The scholarly debate on whether the Sasanians, particularly the early Sasanians like Ardashir I, had any memory of the Achaemenids is as old as the modern study of Sasanian history itself. The grandfather of Sasanian history, Theodor Nöldeke opined that the Sasanians had not preserved any memory of Alexander themselves and all of their memory was borrowed from the Greeks and Romans. He invoked the evidence that the title Hrōmāīg “The Roman,” commonly used for Alexander in Pahlavi texts, is evidence that the Sasanians knew Alexander through the historiography of their rivals to the west.

The debate has raged ever since and has been the concern of almost all scholars who have studied the Sasanians or the early Islamic preservation of their memory in sources such as al-Tabari and even the great Shahnama of Ferdowsi. In a sense, the debate goes far beyond whether the Sasanians (even if we can think of them as a single unit) had any memories of the Achaemenids. The real question is: where are the Achaemenids in Iranian historiography? Where is Cyrus? Where is Darius? Where is Xerxes? Why are there no remains of these grand ancestors in medieval Islamic or Iranian historiography (with rare exceptions, of course, see below for al-Biruni)?

Scholars such as Ehsan Yarshater, A. Shapur Shahbazi, Josef Wiesehöfer, Touraj Daryaee, Rahim Shayegan, Matthew Canepa, Gregor Schoeler, and many others have written about this question in the past 100 years. Their opinions sometimes differ widely (from “there was no Achaemenid memory in the Sasanian period” of Yarshater to “Sasanians used visual culture techniques to harken back to Achaemenid authority” of Canepa) and sometimes are compromising (“mediated memory” of Shayegan or “memory replacement” of Daryaee). Almost all of these, perhaps except Yarshater at some places, accept the basic question that the Sasanians should have kept some memory of the Achaemenids. This assumption is largely based on the fact that, after all, the Sasanians – “the New Persian Empire” of George Rawlinson (1876) – hailed from the same region that the Achaemenids came from, namely the region of Persis or Pars. As scholars have noted, and Canepa (“Technologies of memory in early Sasanian Iran: Achaemenid sites and Sasanian Identity,” 2010: 563-596) has well explored it, Sasanians appear to have purposefully used Achaemenid sites such as Naqsh-e Rostam to legitimise their rule and claim authority. The same appeal to visual memory is also made by Shahbazi (“Early Sasanians’ Claim to Achaemenid Heritage.” 2001: 65), noting the presence of small engravings/graffiti of Ardashir I and probably his father Pabag and his brother Shapur, on the doorjamb of the so-called Harem/Treasury of Xerxes in Persepolis: if they carved ontheir walls, they were claiming their dignity? Surely no one can assume that there was not a claim to a manner of Achaemenid heritage, even if mediated through the Graeco-Roman sources (M. Rahim Shayegan, Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia, 2011: 30-38 and elsewhere).

In my opinion, this argument is at best a form of geographical determinism, arguing that as the Sasanians came from the same region that the Achaemenids did, they ought to have seen the physical remains of their rule, realised the extent of their empire, and aspired to their greatness. This assumes that by observing signs of their local presence, somehow the knowledge of Achaemenid territorial expanse and imperial control would have become available to the Sasanians as well. For lack of a better term, this is a form of pars pro toto (pun intended…) where the Sasanians are expected to adopt an Achaemenid imperial claim, the way for example the Roman historian Herodian claims they did, simply by realising that they hail from the same region as the Achaemenids:

“The entire continent opposite Europe, separated from it by the Aegean Sea and the Propontic Gulf, and the region called Asia he wished to recover for the Persian empire. Believing these regions to be his by inheritance, he declared that all the countries in that area, including Ionia and Caria, had been ruled by Persian governors, beginning with Cyrus, who first made the Median empire Persian, and ending with Darius, the last of the Persian monarchs, whose kingdom was seized by Alexander the Great. He asserted that it was therefore proper for him to recover for the Persians the kingdom which they had formerly possessed.” (Herodian 6.2.2)”

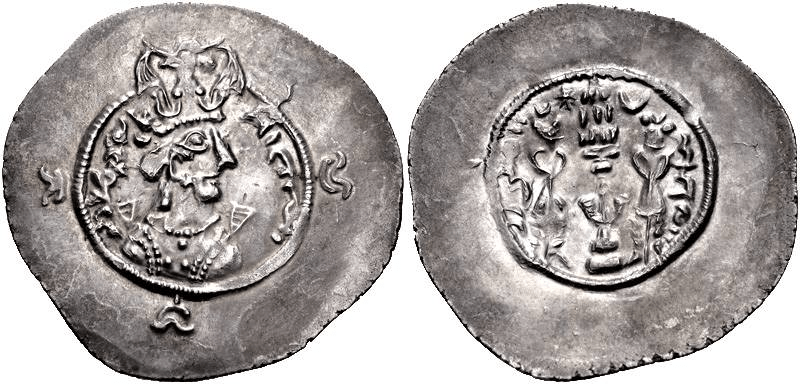

To me, this sounds like overreach, if anything. Early Sasanian rule in fact shows that the earliest Sasanian Kings of Kings, Ardashir and his son Shapur I and grandson Hormizd I – unlike their glorious Achamenid predecessors – stayed safely put in their home province of Persis. There does not seem to be much of an attempt at moving the centre of their rule to Iraq/Mesopotamia, as the Achaemenids had partially done, or claiming centres of Achaemenid rule in Susa or Babylonia. Ardashir ruled from his new capiral in Ardashir-Khurra/Firuzabad in southern Persis, and Shapur went through great trouble to build his imperial city of Bishapur, even after he had defeated the three Roman emperors in Iraq. Persis/Pars seems to have very much stayed a centre of authority and control, a microcosm of Sasanian empire.

There are also no use of other Achaemenid places of authority outside Persis/Pars (Darius’ great inscription in Behistun; the Achaemenid palaces in Susa) to demonstrate such connections. The inscription of Shapur Sakanshah in Persepolis, which belongs to the first century of Sasanian rule, simply mentions the great Achaemenid palace complex as Sadstūn “(hall of) Hundred Columns” and provides prayers to gods, without making the slightest mention of those who had built such an awesome monument. More importantly, despite what Herodian says, the great trilingual inscription of Shapur I himself (ŠKZ), following his defeat of three Roman emperors, says nothing of such claims. In it, Shapur offers praises and devotes fires to many of his ancestors, including his father Ardashir, his grandfather Pabag, and his eponymous ancestor Sasan. Shapur is not known to be a modest person, a fact that if not obvious from ŠKZ, should be glaring from his description of his own archery, from Hajiabad, next to Stakhr in Persis:

The bow shot of mine, the Mazda-worshipping lord Šāpūr, king of kings of Ērān and Anērān, who has lineage of the gods, the son of Mazda-worshipping lord Ardaxšīr, king of kings of the Iranians, who has the lineage of the gods, grandson of the lord, Pābag the King. When we shot this arrow it was before the rulers and the princes of the blood and the grandees and the nobility. We entered this valley and we shot an arrow beyond that marker, but that place where the arrow was shot, there where the arrow set, in that place the marker was placed, it would not be visible from the outside! Thus, we ordered that the marker be placed further up (on the cliff?), so whoever is strong shot, setting foot in this valley, let them shoot an arrow towards that marker, then whoever sets the arrow on that marker, they maybe said to be a Strong Shot! (Shapur, Hajiabad Inscription; author’s translation)

The king’s challenge makes one thing clear: that he cares about his ancestors, particularly those who have ruled in the place where he is leisurely shooting arrows (as Pabag had done). It is wholly devoid of any mention of more glorious local ancestors. The fact that ŠKZ is written in Greek (the Roman language), Parthian (the imperial language of the Arsacid ancestors), and Middle Persian (the newly rising imperial language of the Sasanians) further shows that for the early Sasanians, Persis/Pars was the centre of their power and a microcosm of their empire.

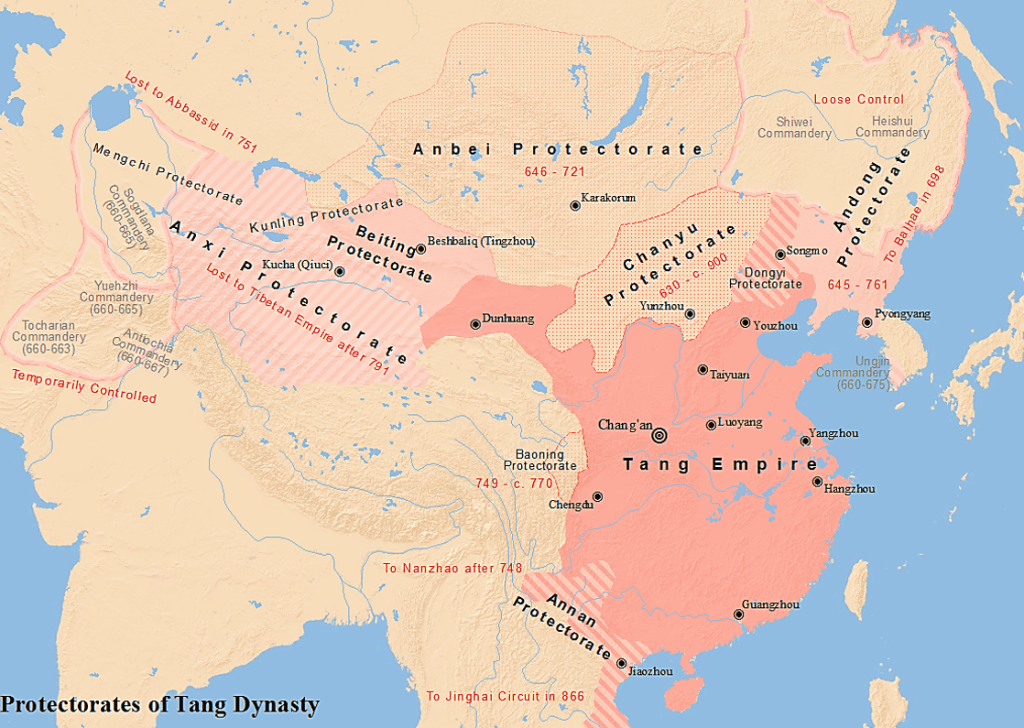

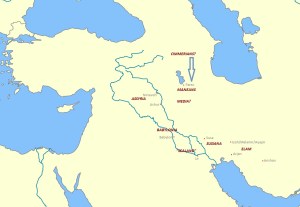

It seems, from his inscription at Paikuli, that the centre of Sasanian power only moved to Asurestan (Sasanian Iraq) and the city of Ctesiphon, when Narseh (293-303), Shapur’s son and fifth successor, defeated his rival, Wahram III (Sakānšāh) near the plain of Sulaimaniyya in today’s Iraqi Kurdistan. Ctesiphon, having been established by the Arsacids as their capital next to the Seleucid city of Seleucia on the Tigris, thus had a symbolic meaning for the Sasanians as claimants to the authority of the Arsacids. Of course, the wisdom of the move was probably questioned when the area was soon attacked by Galerius, the Caesar (second-in-command) of Diocletian, and the household of Narseh temporarily carried off to Roman territories. A later attack by Emperor Julian the Apostate in 363 was soundly defeated by Narseh’s grandson, Shapur II, who had a memorial relief carved showing him standing on the corpse of Julian. This was placed in Taq-e Bostan, a few kilometers west of Behistun, where Darius’ great inscription had been placed 800 years earlier. Yet, there is no reference to the great inscription in Shapur’s relief, or any of the reliefs that came to dominate the site of Taq-e Bostan.

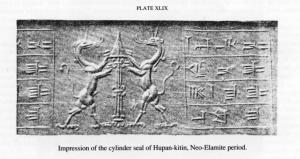

Apart from just not seeing the geographical argument (that the Persis/Pars region by itself should have provided a link between the Achaemenids and the Sasanians) I also find it perplexing why we expect such knowledge at all. Why should the Sasanians have known about the Achaemenids? Or perhaps, more challengingly: why don’t we expect them to have known of the Elamites? After all, sites such as Naqsh-e Rostam, where “technologies of memory” are expected to have reminded the Sasanians of their Achaemenid predecessors, also contain images of the Elamite rulers who preceded the Achaemenids (see Ursula Seidl, Die elamischen Felsenreliefs von Kurangun und Naqs-e Rustam, 1986). So, why are we not wondering about the preservation of the knowledge of the Elamites in the early Sasanian period?

Well, simply put, the reason is because we expect the Achaemenids to have been fabulously famous and well known because they are mentioned in sources that 19 century European historians (eg. Rawlinson and Nöldeke) would have cared about, namely the Graeco-Roman and Christian (ie. Biblical) sources. It is noteworthy also that in fact, historians such as Nöldeke aren’t even concerned with whether the Sasanians remembered the Achaemenids at all. They are more interested in how they had preserved the knowledge Alexander, which Nöldeke strongly posits comes from the Pseu-Callisthenes’s Greek Alexander Romance. The important issue was thus the knowledge of Alexander, the chosen forerunner of Europeans, and the reconfirmation of the accuracy of such knowledge. The discovery of Cyrus’ Cylinder in 1879, in the same year that Nöldeke published his translation and commentary on the Sasanian section of al-Tabari’s History, further highlights this. The discovery proved one thing: that the great king Cyrus mentioned in the Bible was real and he really did invade Babylon and set many captives (including Jews) free, thus confirming the Biblical narrative. The question that was posed was then really this: how is it that native Iranian narratives are not mentioning the dynasties and historical “big man” actors that are so important to the authors of the Greek, Roman, and Biblical sources and their modern European interlocutors?

In the process, little attention was paid to what the Iranians themselves wrote about their history, and what they cared about through such historiography. The narrative of Iranian history in al-Tabari, the Shahnama, Tha’alibi, Rashiduddin, Mostowfi, and tens and hundreds of other books written in Arabic and Persian were simply dismissed. In fact, it is Nöldeke who marks them as mythologies and epics in his monumental, and highly influential and largely unchallenged, work das Iranische Nationalepos (1896). The Pishdadid Dynasty, whose king Frīdōn divided the world amongst his sons and gave the middle part, Ērān, to his son Ēraj, were matched with prototypical Indo-European mythological characters. The Kayanids, whose king Wishtasp/Gushtasp, was the patron of the prophet Zarathushtra, were delegated the role of an Epic dynasty; not as unreal as myths, but not much better either! The challenge was then the last Kayanid king, known as Dārā-ye Dārāyān (simply Dārā son of Dārā) who was defeated by Alexander in the Iranian narratives (Yarshater, “Iranian National History,” CHI.3, 1983). This hadt to be indisputable “history,” because after all, the Graeco-Roman sources agreed that Alexander defeated a Dārā, namely Dārayavahauš, or Darius III…! so when the Iranian historiography matched the Graeco-Roman sources, it was elevated out of Myth ‘n’ Epic slump and placed within the realm of legitimate, European-scholar accepted, History!

This narrative was in fact what the Sasanians did remember, and was probably at the centre of their identity as rulers of their empire, as well as what they reflected as identity on its inhabitants. There is no reason to believe the Sasanians did not remember an ancestor named Darius or Artaxerxes: after all, the founder of the dynasty was an Artaxerxes. Ardashir is just the Middle Persian form of Arta-xšathra, the Old Persian name behind the Greek rendition Artaxerxes. In fact, the King of Kings Ardashir I would have been known as King Ardashir V when he was merely the ruler of Persis/Pars under Arsacid rule: he was the fifth of his name amongst the Kings of Persis in the Seleucid and Arsacid periods (Josef Wiesehöfer. Die “dunklen Jahrhunderte” der Persis, 1994). Additionally, the Persis dynasty (or dynasties) had two kings called Dārā (or Dārev/Dārayān, based on Old Persian Dārayavahauš, Gk. Darius) who incidentally followed each other on the throne too: Dārev/Dārāyān I and II. Significantly, perhaps, the Persis dynasty’s kings-list is glaringly bereft of any Cyrus, Cambyses, or Xerxes. That, somehow, seems important in this debate…

But what is crucial, in fact, is that for the Sasanians, that Myth ‘n’ Epic narrative was as real as the Achaemenids were for the Europeans. If Cyrus is mentioned in the Bible, well, Kavi Wishtaspa/Kay Gushtasp is mentioned in the Avesta (Touraj Daryaee. “The Construction of the Past in Late Antique Persia.” 2006)! For the Arabic and Persian writing historians of the medieval and early modern period, who continued this history and in fact wrote about the Sasanians themselves, the Pishdadids and the Kayanids were as real as the Sasanians. For them, there was no geographical determinism: Sasanians ruled in Asuresran/ al-Iraq, claimed rule over Ērānšahr (never “Persia” which does not appear in any Iranian sources except, in form of Fars, to refer to the region), and considered their rule to be the patrimony of the Kayanids, who ruled from Balkh, by the banks of the Oxus, in what is now northern Afghanistan. For medieval and early modern historians of the Iranian world, up to the 19th century and the encounter with the European historiography, the East, Khurasan, and the city of Balkh, the holy city where Zarathushtra preached and was slain, was the centre. This was where the Pishdadids and the Kayanids had ruled, fought off their Turanian enemies beyond the Oxus, and spread the words of Zarathushtra. Balkh was also were Wahman/Bahman, the grandson of Kay Wishtasp/Gushtasp, had ruled, and it was as the King of Iran that he had sent Khurush/Kurush/Kyrush/Cyrus, the governor of Chaldea, according to al-Biruni, to oust Bukht Nasr (Nebuchadnezzar) from Babylon and set the Jews and others free…

So, to conclude, I like to reiterate my points: that expecting the Sasanian origin from Persis/Pars to be a connection to an Achaemenid imperial memory, any more than to an Elamite one, is logically nonsensical and does not, as the saying goes, hold much water. Secondly, expecting the Iranian historiography to care about the same history that the Graeco-Roman historians, and their early modern European interlocutors, cared about is also, not to mince words, Eurocentric. Aside from missing the point – that history is made up of memories of a chosen past (Daryaee 2006) and is as dependent on what is forgotten as it is on what is remembered. This Eurocentric/Graeco-Roman viewpoint also works to delegitimise what is actually there: 1100 years of written history, from al-Tabari to Etemad-os-Saltaneh. We should perhaps first solve this myopia of ourselves before attempting to figure out why the Sasanians forgot who had built the Persepolis.