The country called Iran is only a part of the historical domain of Iranian cultural. In this text and the ones that follow, the use of the termIran might not necessarily imply what we know today as Iran, bounded by modern borders. Historically, people of modern Iran, Afghanistan, Central Asia, western Pakistan, Caucasus, Iraq, and southern coast of the Persian Gulf have at one point or another been part of the greater Iranian cultural domain. This culture has not been necessarily centred in Iran, and thus does not; in anyway, suggest a chauvinistic or nationalistic view. It is indeed true that many times during the history of Iran and its people, the centres of Iranian culture, and even political power, have lied outside its current borders. Therefore from Iran and Iranian, we don’t always mean the Persian, Kurdish, or Baluchi speaking population of modern Iran, but also the historical population of all other places when Iranian culture has made an impact.

Linguistically, Iran means the land of the Aryans, the eastern branch of Indo-Europeans. A group of Aryans (or Indo-Iranians) who migrated to the Iranian plateau around 2000 BCE from Central Asia, are thought to be the direct ancestors of modern Iranians This has encouraged many historians to start the history of Iran from the Aryan migrations or the establishment of the first Aryan political power, the Achaemenid Empire. At the same time, it is true that long before the influx of Aryans into Iran, different peoples with established civilisations and kingdoms inhabited the country. These dynasties that deteriorated before the arrival of the Aryans or were defeated by them, had an extensive system of international trade and relations with other civilisations of their time, as far west as Egypt and maybe Southern Europe and to China in the east. The history of these people, even if solely for their impact on the invading Aryans, certainly deserves a mention and hopefully deeper investigation. Here, we will briefly mention these civilisation and their international relations, and hopefully investigate their demise under the Aryan rule. But first, a quick description of the Iranian geography seems appropriate.

Geography of the Iranian Plateau

In geological terms, the Iranian plateau is late formation. As late as the Mesozoic era, most of the land was covered by a large sea called the Sea of Tetis. This sea eventually was drained and its remainders became the Caspian and the Black Sea. The lasting effect of the Tetis has been the persistence of salt deserts in Iran and the existence of at least one highly condensed salt lake, Urmiyah. Caspian, the largest lake in the world, also has one of the highest amounts of salt in cubic meter in the world.

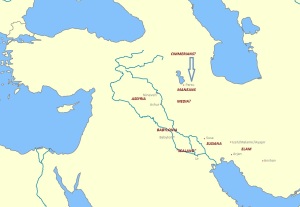

The Iranian plateau today is a land surrounded by high mountains and spotted by warm lowlands. Two important mountain ranges, each with peaks over 5,000 meters high, stretch from the northwestern corner of the plateau, the current Azerbaijan province, to the south and east. The eastern branch, Alborz, boasts the highest peak of the two ranges, Mt. Damavand. The Alborz range creates a high barrier south of the Caspian Sea, making serious impacts on the climate of the plateau. While lush forests and pastures abound south of the Caspian and give it a mild, humid weather, the Alborz prevents the passing of the rain-rich clouds to the inside of the plateau, causing very low rainfall, and thus creating a dry and mostly warm climate south of the mountains.

The second mountain range, Zagros, stretches from northwest to the south and diverts to the east just north of the Persian Gulf. It does not cause as much complications as the Alborz, since the height of the Zagros peaks decrease around the Persian Gulf, allowing more clouds to move over the mountains. In areas were Zagros forms two branches, just south of Azerbaijan; an inhabitable area has been created that shows some of the oldest signs of settlement on the plateau.

Inside the country, there are two major deserts; one, Dasht-e Kavir, around 200 km east of modern Tehran and at the feet of the Alborz range, is covered with sand and is mainly uninhabited. The smaller desert, Lut, is not as dry and provides enough resources for the survival of small communities. These two deserts, both pushing towards the east, have caused the shift of population to the west, north, and south of the plateau.

In addition to the southern Caspian region, two more regions, one north of the Persian Gulf and east of the point of the meeting of Tigris and Euphrates, and the other at the point of meeting of the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Omman, are agriculturally very prosperous. These three areas, Caspian Coast, Khuz, and Persia respectively, have thus provided some of the oldest centres of inhabitation in the Iranian plateau.

The rivers of Iran are few and mainly seasonal. From the major rivers, only Karun in the south, Aras in the northwest, and Sepid-rud in the north flow year round, and only Karun is deep enough for modern navigation. This obvious lack of water supply should have made Iran an unattractive place for settlement. On the contrary, some of the world’s oldest civilisations have formed in or around the plateau. Natural defense and rich resources could be an explanation, as could be the fact that in the pre-historic and early historic times, forests and rivers most likely covered more of the plateau than they do today.

Early Human Life on the Iranian Plateau

Although geologically new, the area of Iran has been inhabited from the very early times. Archaeological excavations have uncovered skeletons of early homo erectus man in Iran and it seems that from the earliest stages of human development, Iran, as a land bridge, has been constantly inhabited.

In terms of civilisations, the evidence carry us to the earliest stages of human settlement. Hunter-gatherers from the high mountains have settled around the plateau as early as 30,000 BC. The origins of most of the earliest human settlements in the plateau are not known and they seem to be local, developing from hunter-gatherer stage to the settled farmers settling in the mountains or plains of southern Caspian coast and northern Persian Gulf. Between 8,000 to 6,000 BCE, the earliest signs of settlement and domestication of animals appears in west and south-western Iran, followed by appearance of painted pottery.

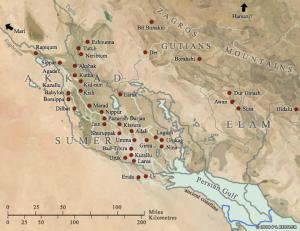

When the Sumerian kingdom was established in the southern most section of Mesopotamia, many tribes had already been settled and were in early stages of state building. The apparent trade between the Dravidian civilisation of the Indus Valley and Sumer passed through the territories of these small states. From the apparent peace and quite that persisted on the area and the flow of trade, we can assume that some kind of agreement was reached for the protection of merchant caravans. The future rise of kingdoms in the area also points to the profit that was gained by them from the passing trade.

I. Early Settlements

The earliest of evidence of a civilisation in Iran come from the southern Caspian region, in present day province of Gilan. Around the village of Marlik, evidence of metal work and pottery have been found that date back to the 5th century BCE. This area seems to have been inhabited by the same people who were settled in eastern Anatolia, proto-Hattians, and Hurrians of later Urartu kingdom. The similarity of art works seem to also suggest close connections with the Kassites of Luristan who later became one of the two dominant civilisations of pre-Aryan era.

The other pre-historic civilisation that is attested in Iran is the civilisation of the people who lived in the city of Sialk, near modern Kashanin central Iran. This walled city attests the oldest fortified settlement in Iran. The danger that these walls were trying to keep out is not known, but it might have come from migrating Kassites who moved from the north and northwest towards the southwestern Iran and the mountains of Luristan. Sialk pottery is close to the Marlik and Kassite pottery, while the signs of metal works are limited. The houses are built from stones, the ready material of the region, and the position of the city suggests a port situation, probably of a larger lake whose remainings still exist as the Daryache Namak (the salt lake) near the modern city of Qom.

II. Kassites

The origin of the Kassites is not known, but their material life suggests close connections to the civilisations of Hurrians and Hattis and even to the Luvian and other pre-Greek cultures of Anatolia and Minoans of Crete. The bronze work of the Kassites is very famous and is used to establish links between the Sumerians, Monoans, Etruscans, and Dravidian civilisation of the Indus Valley/Muhenjudaro. Linguistic research relates the Kassite to the Indo-Iranians, but these are mainly extracted from the names of the deities, mentioned later in the Kassite history. As with the case of the Mitanni, these gods might belong to a ruling class that could have had Indo-Iranian roots, but in general, there is no strong evidence to suggest Indo-European roots of the Kassite. Other local inhabitants of Luristan and the rest of the southwest Iran, Lullubis and Gutians, also do not show any Indo-Iranian characteristics.

Kassites first entered written history in the Babylonian records when they attacked Babylon in a campaign from 2080-2043 BCE under the rule of their first king, Gandash. The Babylonian king, Shemshu-Ilune, the son of Hamurabi the great law-giver, defeated the unorganised Kassite tribes and drove them back to their mountain strongholds. Centuries later, in 1595 BCE, a united Kassite and Gutian force, under the command of Agum-Kak-Reme, attacked Babylon following the Hittite withdrawl, this time successfully, and ruled for about three hundred years, until 1180 BCE. The Kassite dominance of Babylon resulted in the introduction of horse to the Babylonian army, probably the result of earlier Kassite contacts with the Central Asian nomads.

The Kassites also extended their dominance to the Elamite kingdom of southwest Iran and put an end to the Old Elamite kingdom. They extended their lands to the borders of Egypt on one side, and as far north as the Urartu territory in Caucasus and Anatolia. Their last king,Anllil-nadin-akhe, was defeated by the Elamite king and was taken prisoner to Susa where he died in 1180, putting an end to the Kassite power in Mesopotamia. The remaining of the Kassite tribes who had managed to keep their own identity, retreated back to the high mountains of Luristan, where they eventually became part of the strong kingdoms of Elam and eventually the Persian Empire.

III. Elam

Elam, the most powerful and longest lasting civilisation of the Iranian plateau prior to the Aryan arrival, has a complex history. Most of the history of Elam has been recorded by their fierce enemies Babylonians and Assyrians, or by their successors, the Persians, who had a strong incentive to undermine the late Elamite kingdom. As a result, Elamite representation has not been very fair or accurate, and only due to the recent scholarship and reading of Elamite inscriptions we can have a good idea of their culture.

As with the Kassites, we do not have a reliable knowledge of Elamite origin. As far back as 4th millennium BCE, evidence of Elamite settlement in the plains of Khuz (northern Persian Gulf) exist. Researches done on the Elamite skeletons show their racial closeness to the Sumerians and Dravidians of Indus Valley, while their language, at least in its latest form, shows very little connections with these cultures. The Elamite pottery and crafts is strongly influenced by the Sumerian artifacts, as well as Muhenjudaro and Bactro-Margiana cultural artifacts. We might assume that Elamites arrived in their homeland, most likely via the sea from southern Indus Valley region, around 3,500 BCE. Prior to their arrival, the plains of northern Persian Gulf were among the oldest civilised areas in the world history and the site of Susa was inhabited as far back as 4,200 BCE and had come under the rule of the kings of Akkad. When the ancestors of Elamites arrived, they settled in that area under the rule of the Sumerian kingdom of Ur. The proto-Elamites adopted many of the Sumerian cultural characteristics such as the cuneiform writing, which replaced their own original pictographic writing system. Still, they kept their own unique cultural peculiarities such as maternal system of succession and their own religion. Women seem to have held a very important position in the Elamite society. They inherited and willed their property, they ruled and conducted business, and as mentioned before, they were agents of succession in the government. The maternal characteristics of Elamite culture survived up to the Neo-Elamite era (around 750 BCE), around which it started to give way to the Babylonian/Semitic paternalistic system of its neighbours.

The Elamite history has been superficially divided into Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms, based on the Egyptian system adopted by early Orientalists. This division does not hold firmly for Elam, but it is generally used as a matter of convenience. The Old Elamite Kingdom started a period of growth around the early 2nd millennium BCE. They first established their roots in the Khuz area, in the site of Susa(Shusha in Elamite), where Puzur-Inshushinak (r. ca. 2112–2095 BCE) built the first Elamite status in his own honour. Elamites initially attacked and destoryed Ur, and later invaded Babylonia around 2,000 BCE and founded the Larsa dynasty. By that time, they were already the masters of Uruk, Isin, and Babylon. Later, Hamurabi of Babylonia stopped the expansion of Elam, but Babylonians could not stop the great kings like Kutir-Nakhunte to revive the Elamite power a hundred years later (ca. 1700 BCE).

Around 1,600 BCE, Kassites attacked and invaded Elam and annexed it to their empire. This put an end to the Old Elamite kingdom which was ruled successively by Kassites, Babylonians, Hittites, and again by Kassites for another 400 years. In 1160 BCE, Shutruk-Nakhunte, a local ruler of Susa, drove the Kassites out of Elam and established a new dynasty and an Elamite Empire. The culture that allowed the foundation of the Elamite Empire created great cities of Awan, Anshan, Simash and especially Susa, the lowland capital of the Elamites. It also built the great Ziggurat of Chogha-Zanbil, the famous temple of Elam that now remains as the oldest standing archaeological building in Iran.

The aerial view of Chogha Zanbil/Al-Untash-Napirisha

The Elamite Empire was very short lived and it was soon invaded by Nebuchadnazzer of Baylonia in 1120 BCE. For 300 years, Elam, and Susa as its centre, was ruled as a Babylonian protectorate. During this time, the centre of the Elamite power was shifted to the east of their traditional territory and took refuge in the city of Anshan in the Zagros mountains. Elam once again rose to power in 750 BCE and took over their old capital of Susa. This New Elamite kingdom soon became a powerful state and started a campaign against the Babylonians and the new Assyrian Empire. This state, however powerful, could not stand against the overwhelming Assyrian expansion. In 645, Ashur-Banipal, the last powerful Assyrian emperor, invaded and raised Susa to the ground. This was the last blow on the Elamite power which at this point divided into small states and was soon ran over by the rising Median and Persian powers.

Despite its troublesome history, Elam holds a great place in the history of civilisation, especially from the Iranian point of view. Elamites have been accused of cultural stagnation and lack of innovation. While it is true that many of their cultural characteristics, especially writing system, was adopted from the Mesopotamian civilisations, it is undeniable that the Elamites possessed a distinctly Elamite culture. They kept their own religion and built great temples to their gods, including Inshushinak, the protector of Susa, and a goddess who probably became Ardauui Sura Anahita of the Achaemenid religion. Their government system, especially in its succession procedure, was unique for its time. Contrary to the agricultural economy of Mesopotamian, the Elamite economy was based greatly on trade, but also on mining and export of raw material such as tin that was crucial for the powerful empires of Babylon and Assyria. They also for a long while acted as a buffer zone between Mesopotamia and the internal nomads of Iran, in the process, forming a great hybrid culture of Elamite, Babylonian, and Sumerian characteristics.

As far as the later civilisations of Iran are concerned, Elam was the major transmitter of the achievements of older civilisations to the Median and Achaemenid empires. The modified cuneiform that was developed by Elamites from the Sumerian models, constituted an early form of Syllabry that made it possible to create the Old Persian alphabetic cuneiform. Elamite architecture was the model of Achaemenid palaces, and the court procedure of the Persian court was completely modeled after the Elamite costumes. Also, the sciences and knowledge of Elam and Mesopotamia, mathematics and astronomy, was transmitted to the Persian Empire by the Elamite scribes who made their language one of the three official languages of the empire. Maybe the greatest tribute paid to Elam was the selection of their old capital, Susa, as the main capital of the Achaemenids. Cultural legacy of Elam has affected their successors more than many might imagine.

IV: Other Civilisations

To the north of the Kassites, there lived a group of people called Hurrians who were probably the native inhabitants of the southern Caucasus. They spoke a language unrelated to all other languages around them, and they seem to have spread quickly around the landscape in the second millennium BCE. Their area of influence stretched westwards to the Van Lake area and made them neighbours of the Hatti and later the Hittite Kingdom. Around the 1400 BCE, a group of Hurrian people formed a kingdom called the Mitanni in the areas of modern Kurdistan and eastern Turkey. The Mitannis adopted the Assyrian cuneiform and have thus left us with a few written documents of their civilisation. From these documents and also from an important inscription detailing a Mitanni peace treaty with the Hittites, we know that at least the ruling class of the Mitanni kingdom were from an Indo-European and specifically Indo-Aryan background. A manual for training of horses uses many Indo-European names for horse accessories, and in the aforementioned peace treaty, we have the name of many Indo-Aryan deities included in the pantheon of Mitanni gods. This has for long puzzled the historians, since the distance between the Mitanni and the rest of the Indo-Aryans who at the time lived in Central Asia and Afghanistan is great. Conventional scholarship suggests a migration of Indo-Iranians from the plains of Central Asia to northeastern Iran and then south to the Indus Valley. If this view is accepted, the existence of a semi-isolated Indo-Aryan ruling class in western Iran seems highly confusing. A possible suggested answer is the migration of a branch of Indo-Iranians from the northern plains of the Caspian Sea down the Caucasus and into western Iran. This and other suggestions seem to be kept at the level of theory in the absence of empirical evidence in their support.

Urartu, another Hurrian nation, also formed a civilisation of the Iranian plateau. Their kingdom was very successful in its relations with the dominant powers of the time, Assyrians and the Hittite. Urartu formed a trade confederation that benefited from the Assyrian and Hittite desire to access the tin and gold mines of Iranian mountains. With the wealth coming from their trade, the Urartu built lasting tributes to their civilisation whose remains still stand around northeastern Iran and eastern Anatolia. The later Armenian kingdoms claimed descent from the Urartans, and the name of the great mountain of Armenia, Mount Ararat, comes from the name of the Urartu people. This civilisation ceased to exist sometimes before the rise of the Median kingdom in the southern borders of their territory (ca. 650 BCE), but it left lasting influences, especially in architecture, on the kigdom of the Medes.

Further Readings

Cameron, George G. “Ancient Persia.” The idea of history in the ancient Near East (1955): 77-97.

Cameron, George Glenn. History of early Iran. New York: Greenwood Press, 1968.

Postgate, Nichol. Early Mesopotamia: Society and economy at the dawn of history. Routledge, 1994.

Potts, Daniel T. The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian state. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Van de Mieroop, Marc. A history of the ancient Near East: ca. 3000-323 BC. Vol. 1. Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

Waters, M. W. A survey of Neo-Elamite history, University of Pennsylvania PhD Dissertation (January 1, 1997).

P. E. Zimansky, Ancient Ararat. A Handbook of Urartian Studies, New York 1998